Stravinsky Was a Leader in the Revitalization of in European Art Music

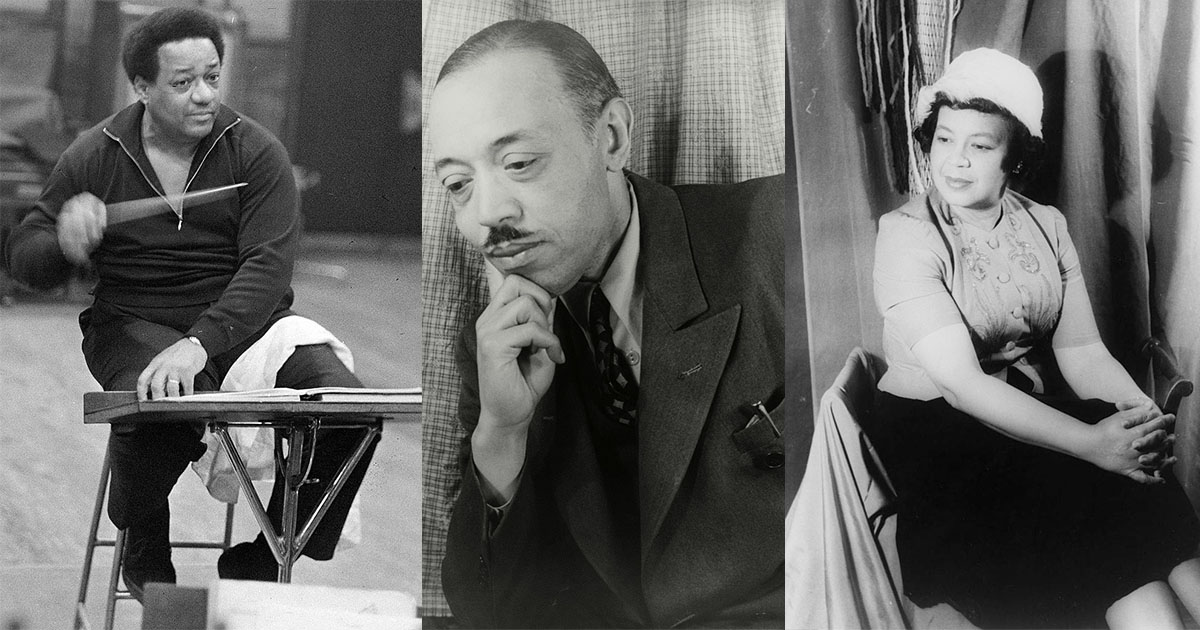

Left to right: conductor Dean Dixon, composer William Grant Still, and composer Margaret Bonds (Wikimedia Commons)

It may seem improbable today, only some 75 years ago, classical music was a lingua franca for the average American, regularly heard and pervasive in mainstream pop culture. Motion picture soundtracks of the Hollywood studio era either directly quoted or deliberately evoked the vocabulary of 19th-century symphonic and operatic literature, with many of the flick composers themselves (Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Max Steiner, and Franz Waxman, amidst them) émigrés from the European concert earth. Classical musicians were frequently portrayed as romantic or tragic characters in the movies, on radio, and in legitimate theater, regarded not as aristocracy types but every bit Everymen. Clifford Odets's popular 1937 play Golden Boy (later a movie and a Broadway musical) was nigh a young homo torn betwixt beingness a prizefighter and a violinist, a dilemma unlikely to accept befuddled Muhammad Ali or Tyson Fury.

Comedians Jack Benny and Henny Youngman came on stage with violins as props; both played the instrument competently though driveling it humorously during their standup routines. The trope of the struggling musician or composer finally making information technology to Carnegie Hall was portrayed in countless movies, including a 1947 film actually titled Carnegie Hall. In the 1946 Warner Brothers movie Deception, Bette Davis two-times her cellist lover Paul Henreid with classical pianist-composer Claude Rains; the same year, the same studio put out Humoresque, in which arts patroness Joan Crawford commits suicide Virginia Woolf-style when her love thing with the young concert violinist she has sponsored (John Garfield) goes sour (Isaac Stern dubbed Garfield's violin-playing scenes). Could whatsoever film credibly essay a similar plotline in today's civilization?

In this before era, popular civilization fed off the notion of a Western catechism of great music. Familiar classical ballet tunes were spoofed by Daffy Duck and Bugs Bunny in Warner Brothers' Looney Tunes cartoons. The Paul Whiteman band quoted themes from Igor Stravinsky in jazz arrangements, Broadway show orchestrations quoted Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, and Antonín Dvořák's Humoresque was dished upwards by both novelty piano star Zez Confrey and jazz virtuoso Art Tatum. Pianist Hazel Scott specialized in "swinging the classics" and did and so in nightclubs and the movies. Operetta films starring Jeanette MacDonald and Nelson Eddy were immensely popular, and opera singers Lily Pons, Risë Stevens, Lauritz Melchior, and Ezio Pinza starred in Hollywood movies. Popular radio personality Oscar Levant played non simply the wisecracking sidekick but as well the Khatchaturian "Sabre Dance" on the piano in the Fred Astaire–Ginger Rogers moving picture The Barkleys of Broadway, and pianist José Iturbi performed Franz Liszt's Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 in the 1945 Frank Sinatra-Gene Kelly film musical Anchors Aweigh. (Levant'southward 1940 volume A Smattering of Ignorance was largely about classical music business gossip. It was a bestseller.) Comic percussionist Spike Jones'south band on radio and TV did "musical depreciation": zany, anarchic sendups of tunes from Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and even Anton Rubinstein adjacent with striking parade numbers, because the longhair tunes were every bit well known as the popular ballads.

Commercial advertising supported broadcasts of classical music up to the 1960s. The Bell Telephone Hr and the Voice of Firestone featured performances by pianists, violinists, and opera singers on radio and TV from the 1930s to the 1960s. Texaco sponsored both the weekly Saturday Metropolitan Opera broadcasts and the Milton Berle TV show Texaco Star Theatre. RCA dominate David Sarnoff created the NBC Symphony Orchestra for conductor Arturo Toscanini, and alive television broadcasts of the concerts, from the late 1940s to early '50s, were sponsored by Full general Motors. NBC also broadcast an extended interview with Stravinsky in his habitation studio. Non to exist outdone, William Paley'due south CBS boob tube deputed Stravinsky to etch The Flood for CBS and broadcast Leonard Bernstein's Young People'south Concerts. The well-nigh widely watched TV diversity program from the late 1940s to the early '70s, CBS's Ed Sullivan Show, adopted vaudeville'due south original format of alternating lowbrow circus acts (tumblers and acrobats) with High Art (Charles Laughton reciting from the Book of Daniel). On any given Sunday dark on Ed Sullivan, 1 could lookout ventriloquist Señor Wences taking a drink of water while his painted hand boob Johnny was still speaking clearly, followed immediately past coloratura soprano Roberta Peters singing an aria.

Classical music was also a pawn in the chess game of geopolitical strategy during the Cold War. The CIA in 1950 established the Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF), an anticommunist forepart group to promote avant-garde American artists (including composers) as exhibits of American cultural freedom (a roughshod irony, since at the same time, some were being summoned to testify before Senator Joseph McCarthy's committee). Composer Nicolas Nabokov (a cousin of writer Vladimir), called every bit 1 of CCF's leaders, became i of the most politically influential musicians in the Western globe for some years afterward. (His story was dramatized in the 2013 play Nikolai and the Others produced at Lincoln Center.) Henry Pleasants, the longtime music critic of the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, moved to Europe afterward the war and became a spy for the CIA, his cover exposed only later on his death in 2000. When young Texas-born pianist Van Cliburn won showtime prize at the International Tchaikovsky Competition in Russian federation in 1958, information technology was a page-1 event in newspapers worldwide. Cliburn was given a ticker-tape parade in New York upon his return from Moscow. No classical musician has been accorded such an award since. It should be added that during these same years, classical music appreciation classes were a staple of public-school curricula in most parts of the country (and have not been for decades).

Tocsins accept rung perennially for the autumn of classical music's identify in the mainstream, merely now, in the 3rd decade of the 21st century, a wholly new paradigm governs: we no longer have a cultural mainstream. We have a broadband crazy quilt. SiriusXM radio has some 150 music channels of every genre: only three of them are classical. For the public, "music" is now divers by the other 147. We alive in multiple cultural taste silos. Moreover, even in classical music, musical structures that crave patient, single-focused attention to cumulatively developing sequential forms, such as sonatas and symphonies, are well-nigh equally obsolete as epic poems; they don't have buy on younger people for whom multitasking, TikTok, and low-level perpetual attention deficit disorder are the new cognitive norms, and for whom surface grooves are typically the meat of the music experience. Curiously, traditional, plotted, high-literary novels withal sell, yet musical compositions based on repeating waveforms, where abrupt changes in phase are taken as developmental musical events, have largely superseded older narrative ways of organizing art music. Digital engineering itself seems to take reshaped the content and very notion of what constitutes long-class music; 21st-century compositions sometimes seems like an emulation of the electric tools that produced them.

The ecosystem that birthed classical music in previous centuries is very different from the world today. Today every urban pedestrian listens to her ain soundtrack or playlist through earbuds while inbound city crosswalks; prior to widespread electrification, the only "soundtracks" were live performances or those in the mind'southward ear. People did non ride in horse-drawn carriages or on steamships and early locomotives while listening to music (showboats and the Titanic excepted). Without 21st-century applied science to outsource one's personal retentiveness to online storage or to admission at a click the databases of Google, Wikipedia, and YouTube to acquire knowledge instantly, human memory earlier 1900 was necessarily a more muscular and retentive faculty. Composers could rely only on their memories of alive performances and score-reading abilities. Nevertheless in just such an environment, impoverished of mod conveniences and 24/vii exposure to music, all the past masterpieces of musical art were created, voluminously, with low-tech tools.

Conveniently forgotten is that until the invention and adoption of the typewriter in the 19th century, the literature of the entire history of the world—novels, plays, and poems, every bit well every bit musical scores—was slowly created in longhand with metal or quill nibs dipped in liquid ink, either in daylight or under the illumination of candles, or oil or kerosene lamps, or gas lights. Mistakes could non be erased, only blotted out. Copying could only be washed manually; scribes were a necessity in the chain of labor; paper was dear. How did so much become written under such weather condition? Now composers have the ability to recopy without manually recopying, to cut and paste without throwing out paper, and to click instantly on almost any recording or score that has e'er been published. In fact, a vast amount of specialist information tin can be instantly accessed without actually being learned—it is merely momentarily attached rather than earned and mentally banked by deadening assimilation.

As then much of this data is couched on the Internet in photos, videos, illustrations, and synchronized music (an assemblage once quaintly termed "audiovisuals") rather than language, the skills required to navigate this push-push button magic carpet are at present termed "media literacy." Media literacy is becoming the dominant mode of literacy, threatening the dominance of millennia of traditional scriptorial literacy. And its trend to reduce communication to rapidly flashed visuals and audio bites cheapens the appreciation of great art and music, eliminating depth, sometimes reducing complex achievement to mere celebrity, and atrophying the muscles of memory, since flashcard storyboard summaries don't linger in the mind as enduringly as the ecstatic passion of Tristan und Isolde or the convolutions of Ulysses, which are processes that have to be endured the long fashion to be appreciated.

Perversely, the instantaneous click-access to all historical knowledge on the web seems to take given ascent to a general indifference to history among the immature. Millennials who have known only the postdigital environment tend to interpret history only through their current cultural biases and social media shares. As a outcome, the very concept of a historical catechism has become toxic, and with classical music no longer the histrion information technology was 75 years agone, this antihistorical attitude threatens to drive appreciation of classical music fifty-fifty further from its one-fourth dimension pride of place in general culture. Classical music has been especially susceptible to charges of a toxic canonicalism that shortchanges other cultures' contributions.

Can annihilation exist done to effect a rapprochement between the old and the new paradigms and then that the heritage of classical music tin be revivified for younger generations? Ane possible answer is being suggested by the scholar and critic Joseph Horowitz in his new book Dvořák's Prophecy and the Vexed Fate of Blackness Classical Music. Horowitz seems to say that it'southward not necessary to topple approved classical music idols as if they were the Buddhas of Bamiyan, because a rich parallel heritage of African-American classical music has been hiding in evidently sight all along. He has causeless the office of a skilled art conservator who is cleaning up an former master, removing an overlayer to disclose a pentimento: an underlayer that is a veritable classical music 1619 projection. And at the aforementioned fourth dimension, in a series of half-dozen companion videos that he narrates (Dvořák's Prophecy: A New Narrative for American Classical Music, produced by Naxos), Horowitz goes a practiced way toward remediating the problematic aspects of media literacy, sound-bite epistemology, Snapchat concentration spans, and anhistorical narcissism that bedevil our culture today.

Horowitz's arguments are multiple. He contends that a visiting European composer, Antonin Dvořák, founded a new school of Americanist composition in the 1890s, based upon indigenous Black and Native American music (i.e. spirituals and tribal ritual songs), that was abased past mainstream 20th-century American classical composers; that several African-American composers were the truthful and only exponents of the Dvořák school merely were severely neglected by classical music power centers, until very recently; that Charles Ives and George Gershwin (and Louis Moreau Gottschalk before them) embody the truthful autochthonous American art-music tradition; and that the American populism of Aaron Copland, Virgil Thomson, and Roy Harris is synthetic and inauthentic. It is a volley of iconoclastic salvos, not unlike that of Henry Pleasants's book The Desperation of Modernistic Music (1955), though Pleasants argued the antinomy was between abstract, atonal, modern fine art music and jazz, favoring the latter equally America'southward true classical music.

Horowitz also argues that the chief champion and practitioner of Native American–based art music, the white Anglo-American composer Arthur Farwell, has not only been unfairly neglected, but is too still vexed by the charge of cultural appropriation. These and other questions are teased out both in his book and in the accompanying six videos, which focus on Dvořák, Ives, Black composers, Bernard Herrmann, Lou Harrison, and Copland, respectively. As a group, these videos (along with a CD of Farwell's music) sweep together a vast canvass of miscellaneous, sometimes tenuously related Americana, though all are interestingly told. The video documentaries eschew the Ken Burns fashion of rapid montage and instead get into deep focus. Talking heads speak at length rather than in audio bites. The music on the soundtracks, performed by the Washington, D.C.–based PostClassical Ensemble (of which Horowitz is executive director) and conducted by Affections Gil-Ordóñez, is not interrupted past hyperkinetic visual montages or multiple voiceovers. It's the documentary equivalent of "slow food"; there is room to absorb and think and remember.

Appropriation is a vexed word now, but any reckoning of American popular music history that does not acknowledge the chief, progenitive influence of African-American music is irresponsible. In fact, the history of American popular music is a history of cultural appropriation. Minstrel shows appropriated the West African music of plantation slaves. Vaudeville appropriated minstrel-show sketch one-act and music. Irving Berlin appropriated ragtime with his vocal "Alexander'due south Ragtime Ring." Paul Whiteman became known as The Male monarch of Jazz, though his very proper noun betrays the appellation. (Equally ironic, the greatest Blackness orchestra leader of the 1910s was named James Reese Europe.) Jazz was appropriated by European white musicians from Stravinsky to Maurice Ravel to Darius Milhaud, and by classical pianists like the Austrian Friedrich Gulda and the Russian Nikolai Kapustin, who improvised and composed in a jazz idiom. Rap, originating in Black urban areas, has traveled the world and is now appropriated by (or, perhaps more benignly stated, practiced by) every national culture.

Black musical civilisation has every correct to feel the victimhood or homage of appropriation—except in classical music, every bit Horowitz suggests. At that place, he posits the contrapositive: that American classical music should accept adopted the popular music paradigm, and enlivened the fine art music tradition with the same Afro-indigenous influences as did folk and popular music. In non doing so, he claims that classical music has lost some of its potential expressive power, and he argues that one path to revitalization in the 21st century is to reclaim the Dvořákian arroyo.

This is like saying that Nikos Skalkottas, the short-lived Greek composer, was all wet when he wrote anguished, atonal, scores in the manner of Alban Berg, and should accept stuck to his tonal orchestral suites of native Greek dances. But both styles of Skalkottas are strong in their carve up ways. On close inspection, the authenticity bug are entangled, not binary. Many made-in-American folk-art genres were, from nativity, admixtures of Anglo and Afro origin. Tap dancing is Afro-Celtic: it evolved in the mid-19th century from a fusion of the West African rhythmic trip the light fantastic of slaves and the clog and step dancing of Irish immigrants. The Irish greasepaint dancer John Diamond and the Black dancer William Henry Lane (known as "Chief Juba") faced off in jig contests in Manhattan'south Irish Five Points district in the 1840s. Rock 'n' roll is a 1950s marriage of what was theretofore known in the music trades as Blackness "race music" and white "hillbilly" music; the genre owes a debt to both.

Are classical symphonies built on Black ethnic music invariably as successful as William Levi Dawson'south Negro Folk Symphony? The great stride pianist and composer of "The Charleston," James P. Johnson, likewise composed classical scores based on such sources, only the New Grove Dictionary of Jazz states that "some commentators take questioned the success of Johnson's orchestral compositions." Duke Ellington's symphonic work Black, Brown, and Beige was described by its sympathetic orchestrator Maurice Peress, who knew Ellington and recorded the piece, as "enigmatic and complicated … hard to fathom." Where does the Dvořák theory leave the work of Black American composers similar Ulysses Kay (1917–1995), Howard Swanson (1907–1978), Julia Perry (1924–1979), and George Walker (1922–2018), all of whom wrote first class symphonic and chamber music in the prevailing European-derived cosmopolitan idioms favored by their white American and European contemporaries, and whose work was performed, recorded, and acclaimed in their lifetimes? The Dvořákian model's nearly plausible later descendant may have been the mid-20th-century "third stream" music propounded by composer-conductor Gunther Schuller: atonal/tonal compositions that made a fusion between jazz and high modernism. Actually, the 3rd-stream idea is alive today in the symphonic works of Wynton Marsalis, notably his Violin Concerto.

In classical music, practical situations have often led to foreign bedfellows. The African-American usher Dean Dixon, whom Horowitz cites, in the 1950s conducted and recorded Rhapsodie Nègre for pianoforte and orchestra by John Powell, a Virginian who was "quite a figure in the century's early decades," according to Virgil Thomson. But Powell was likewise an outspoken, rabid segregationist. Why did a white supremacist etch a Rhapsodie Nègre, and why did a Black conductor record information technology, and why did Powell, who was alive at the time, not object to Dixon'south conducting the recording? Possibly for reasons similar to Wagner's blessing of Hermann Levi, a rabbi's son, to conduct the premiere of Parsifal, the well-nigh Christian of operas? Or no?

Why did some white musical artists in the 1920s pass for Black (Aileen Stanley) on records (Blackness Swan Records) and some Black musical artists in the 1920s (William Grant Still) pass for white on records? (When However'southward last name appeared on Whiteman band records as arranger, nobody just a few insiders knew that he was Blackness.) Let us as well not forget Fela Sowande, the Nigerian composer whose euphonious African Suite for string orchestra is written in a conservative 20th-century European idiom notwithstanding sounds indigenous.

Dvořák'due south Prophecy subsumes Ives into its overarching thesis, citing the composer's leitmotivic use of American marches, hymns, and popular ballads and folk songs equally kindred to Whitman and even Samuel Clemens. Horowitz points out that Harmony, the daughter of Clemens'southward all-time friend, Joseph Twichell, married Ives (apparently unaware that this life-imitating-art incident was made into fine art by composer Robert Carl and librettist Russell Banks in their opera Harmony, performed at the Seagle Festival in upstate New York last year). He argues that both Ives and Gershwin were no mere primitives in the fashion of Pocket-sized Mussorgsky, simply technically achieved composers. Elite stance has not always concurred. That impeccable musical workman Samuel Hairdresser told an interviewer of Ives in 1979, "Information technology is now unfashionable to say this, but in my opinion he was an amateur, a hack, who didn't put pieces together well." Elliott Carter, who knew Ives, found a "disturbing lack of musical and stylistic continuity" in his music, and even Ives champion Bernard Herrmann said, "He never got his music into shape for a performance. … People looking around at Ives to discover his musical technique or form are all wasting their time, considering he didn't take any." In 1958, withal, Leonard Bernstein, whom Horowitz quotes every bit damning Ives with faint praise, did extol the composer as "the Washington, Lincoln, and Jefferson of American music." Why does Horowitz say Virgil Thomson and Aaron Copland advocated pastlessness, when Thomson's own music seems the very apotheosis of a cornball American Arcadia with its "plagal cadences" (every bit Leonard Bernstein once put information technology), and Copland's greatest successes were modeled on the folklore and fifty-fifty tunes of earlier American centuries (his ballets Rodeo, Billy the Kid, and Appalachian Leap, and his Former American Songs)?

Horowitz briefly mentions the American ethnomusicologist Natalie Curtis. A closer await at her pioneering piece of work better illustrates how problematic the pluralistic mélange of autochthonous American music is. (I am indebted for the following data to the researches of my colleague Cora Angier Sowa.) Built-in into wealth in a Henry James–similar Manhattan milieu in 1875, Curtis was a society debutante pianist who moved out West to recover from a nervous breakup. There she started to collect cowboy music. Some of the cowboys were Amalgamated veterans. Some were freed Black slaves. Some were Mexicans. (So much for ethnic consistency of ethnic music.) Soon she met Charles Fletcher Lummis, a Harvard Brahmin who had become a champion for the preservation of native southwest Indian culture. Lummis led a movement to fight the U.S. authorities's forced assimilation of the Hopi Indians into white Anglo culture. Living in Arizona, Curtis recorded the Hopi music using an Edison cylinder motorcar, transcribed it, and later published it. (The American photographer Edward Curtis, who was unrelated to Natalie Curtis, also fabricated extensive sound recordings of Native American music in situ with Edison cylinders.)

The European composer-pianist Ferruccio Busoni, who had lived and worked in Boston a few years before Dvořák came to New York, acquired Curtis's book (she had once studied piano with him) and equanimous big concert pieces on its Hopi themes (the Indian Fantasy for pianoforte and orchestra and the Indian Diary for solo piano). The 1915 premiere of Busoni's Indian Fantasy by the Philadelphia Orchestra was conducted past Leopold Stokowski—the same conductor who would premier Dawson'southward Negro Folk Symphony with the aforementioned orchestra 19 years afterward.

Stokowski told the press afterwards the 1915 Busoni performance: "I consider this the most important new step in the evolution of music since Debussy first began to break fresh paths in tonal and harmonic relations. It will take a very deep influence on the trend of music in the future." Simply, somewhat not in keeping with Horowitz's premise, it has not. Nor did Stokowski's later championship of the estimable Dawson symphony catch on with other conductors.

In 1904, Curtis went to the Hampton Institute in Virginia to collect the folksongs of Native Americans who had been co-enrolled there with sometime Black slaves. She then undertook the projection of recording with Edison cylinder and transcribing all the voice parts of choral African-American spirituals, work songs, play songs, and similar works. Publishing the results, she appear that there were 4 types of folksong in the United states: Native American, African American, mountain white (i.e. Appalachian), and cowboy (i.e. southwestern). Later, she fabricated a collection of songs from two African immigrants at the Hampton Constitute, one from Portuguese East Africa, and one from Zululand in South Africa. Curtis moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico, in 1916 and married the painter Paul Burlin. In 1921, the Burlins moved to Paris, where one tragic twenty-four hour period, Natalie was striking by a speeding ambulance and died of her injuries at historic period 45.

One problem with Native American song and dance as a sourcebook for art music is that the music, different African and African-American music, is express to monophony with unpitched rhythmic accompaniment, and therefore art-music composers, even the sympathetic so-called Indianists (Farwell, Charles Wakefield Cadman, Victor Herbert in his opera Natoma) had to invent convincing supporting harmony and formal architecture to convey the Amerindian color. But late-19th-century romantic harmony was not quite up to this task, and as a result, many of the Indianist composers' works sound kitschy, similar Thurlow Lieurance's "By the Waters of Minnetonka." Farwell's Indianist works use the comfortable tonal Romantic harmonic language of Edward MacDowell spiced with a soupçon of dissonance and French impressionism. Busoni'due south Indian pieces are more successful, perhaps because they set ethnic-sounding transplants of the Hopi melodies and rhythms with more daringly athwart harmonic linguistic communication and a freer utilize of tonality bordering on atonality. (Farwell's after cosmopolitan music for orchestra is craggier harmonically, and sometimes sounds like American Havergal Brian.) Horowitz's schema of putting Farwell and Roy Harris at reverse poles of the aesthetic dissever is amusing in that Farwell was Harris's first instructor and mentor, the musician well-nigh responsible for urging Harris to get a composer.

It should be noted that John Powell, the white racist composer, too nerveless Appalachian music. And then did the German émigré Kurt Weill, for his all-American folk operetta Down in the Valley. Only the real primary of cowboy music collection may have been the Texan David Wendel Fentress Guion, a pianist who studied with Leopold Godowsky in Europe and came back to the States to popularize "Home on the Range" and write pianoforte arrangements of "Turkey in the Straw," "The Arkansas Traveler," "The Harmonica Role player," and "The Scissors Grinder," that are too difficult for all but professional person virtuosos to play. In the 1920s and '30s, his songs were widely broadcast on the radio in ring arrangements, merely somehow Copland and Thomson never seemed to mention Guion'southward work equally an influence on their own forays into American musical folkways. Guion is every bit undeservedly forgotten as Farwell.

Horowitz compares Copland's jazzy Piano Concerto invidiously with Gershwin's, and quotes condescending statements almost Gershwin from Copland and Thomson. I recall they simply were envious of his success. Here's a personal anecdote. In the mid-1970s, I studied music composition with Gail Kubik, a one-fourth dimension Pulitzer Prize winner and an associate and slightly younger contemporary of Copland and Thomson who likewise wrote Americana-flavored music. I day, Mr. Kubik inquired what modern composers I liked. When I mentioned Gershwin, he winced and made some terse comment of displeasure. I had the distinct feeling he was jealous.

While Native American music is harmonically limited, Gershwin wrote in a singularly rich, polyglot, kaleidoscopic harmonic idiom—at one time bluesy, African, European, New York, middle-American, chromatic, Hebraic, with hints even of Latin and Asian—that has never been imitated. Contempo scholarship by Howard Pollack and others has shown that Gershwin was a much more self-conscious, finished composer than previously suspected. It may be a thing of dispute, though, whether to credit, as Horowitz does, Porgy and Bess, equally great every bit it is, with greater cultural vitality than Samuel Hairdresser'due south Adagio for Strings, Leroy Anderson'due south Sleigh Ride, or Bernstein's Due west Side Story–—or even the operettas of John Philip Sousa (the original source of many of his march tunes)—to take some of the other examples of pieces written by Americans of the "non-Dvořákian" schoolhouse that permanently entered the American commercial vernacular in the 20th century.

Horowitz focuses on three Black composers who wrote symphonies in the 1930s and 1940s that vicious into neglect: Nonetheless, Dawson, and Florence Cost (he also mentions Margaret Bonds). He gives honorable mention to the Canadian-born Nathaniel Dett, who had been manager of Virginia'south Hampton Institute and its choir during the years Natalie Curtis did her research in that location. (This writer heard the Cincinnati Symphony's performance of Dett'southward oratorio The Ordering of Moses live at Carnegie Hall in 2014.) Dett was peradventure the only one of the four whose music was championed repeatedly by a leading white musician during the prewar era: the composer and pianist Percy Grainger. Grainger not just regularly programmed selections from Dett's In the Bottoms Suite in his recitals in America and Australia, he besides included Dett'south music in his radio lectures and made several recordings of Dett's Juba Dance. At a 1916 concert in Hamilton, Ontario, that featured both Grainger equally pianist and Dett's choral piece "Listen to the Lambs," Grainger gave an impromptu speech, chastising the audition for non knowing that this "highly gifted musician and composer" (his words, in a letter) was Canadian. Grainger produced a concert on May 3, 1925 at Carnegie Hall that featured Dett conducting his chorus in his Negro Folksong Derivatives and Grainger conducting Natalie Curtis'southward Memories of New Mexico, Franz Schreker's Sleeping accommodation Symphony, Paul Hindemith's Bedchamber Music No. 1, and Edvard Grieg's Lost in the Hills.

Horowitz's volume frequently laments the American musical catechism's fail of a useable past in regard to Black composers (and other composers) but omits applying the same critique to more recent examples of neglecting a useable past. Information technology'south dandy that the Metropolitan Opera commissioned Terence Blanchard to compose Fire Close Upward In My Bones, and volition shortly present a revival of Anthony Davis'south 10. Simply what about reviving William Grant Still's worthy opera Troubled Island, which was produced in 1949 by the New York City Opera but rejected past Rudolf Bing of the Met? Or any of Yet's eight other operas? What about one of Ulysses Kay's v operas, especially his Jubilee, based upon African-American writer Margaret Walker'due south novel of the same proper name? Walker threatened to sue if the opera were performed once again later on its initial performances, but since her death, efforts have been made to revive the work. Why has the tragically brusk-lived biracial pianist-composer Philippa Duke Schuyler practically disappeared every bit a cultural figure (she was once a celebrity)? Don Shirley is well-known now as a consequence of the movie Green Book, simply some of his contemporaries, like pianist-composers Robert Pritchard and Natalie Hinderas, are still little known.

In most cases, Black composers face the aforementioned difficulties clawing for performances that composers of other groups confront. Furthermore, Black composers write in equally many unlike idioms as white composers or Asian composers. There is no dearth of contemporary Black composers, from pre–Baby Nail to Generation Z, who compose concert music in the cosmopolitan idiom, the tonal/atonal/consonant/anomalous mélange that was the common tongue of the 20th-century classical music globe. Alvin Singleton and Adolphus Hailstork represent the elders of this group, just information technology extends to Gen Xers similar Jesse Montgomery and Gen Zers like Quinn Mason, all working in an eclectic mix of styles, some traditional, some nontraditional, some abstract, some ethnic-based. (20-first century Native American composers of classical music have emerged more than slowly than Native American authors of fiction. While Louise Erdrich and N. Scott Momaday are long established as novelists, composer Jerod Impichchaachaaha' Tate does not nevertheless have a lot of company.)

A typical current case is the prolific mid-career Baby Nail composer Kevin Scott. Scott is eclectic in the best sense of the give-and-take. He is writing an opera nearly Fannie Lou Hamer. His work includes elegiac orchestral homages to Betty Shabazz (A Passion of Our Time) and Arthur Ashe (A Signal Served), neoromantic tone poems that pay homage to the groovy film music of the Hollywood era (Lazy King of beasts, Ben Hur), only for the greater office of his output, Scott composes in a powerful, abstract, atonal, cosmopolitan, most neo-Bergian idiom (including his bicycle of Anne Brontë songs and six string quartets). He does not play or etch jazz or quote from folk music. For all his diversity of styles, Kevin Scott'southward music does non fit into a niche. And that's a strength.

Jubilant what Horowitz interprets as the lost Dvořákian school of American music rightfully bestows many past Black composers not just with approved recognition but also with inclusion in American music history textbooks. (A few of them had already appeared in Virgil Thomson'southward 1971 book American Music Since 1910. The best dominance, Eileen Southern'southward magisterial The Music of Blackness Americans: A History (1971), should be in every music history course syllabus.) Withal uncovering new understandings of a neglected role of our musical history may non exist the same thing as finding prescriptions for future creative evolution. Margaret Bonds and Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson composed much music based on spirituals and jazz, but how many Black concert music composers today volition apply those languages as an sectional foundation for their limerick the manner Arnold Schoenberg exclusively used the 12-tone row? The folk music of contempo generations is international pop. Pop civilization itself may already accept replaced folk elements as a model for contemporary vitalization, judging from works of composer Michael Daugherty similar Route 66 and the City Symphony, the classical mashups past violinist-composer Ezinma of Beyoncé and Megan Thee Stallion, and many works by minimalist composers, especially those that fuse minimalism with neoromanticism.

You have to adore Horowitz's ambition in his book. Dvořák's Prophecy makes many vigorous arguments and strenuously tries to stuff a huge panoply of American music in virtually too brusk a space, which sometimes leads him into overcompressed, crabbed language to drive home his points. Just generally, the management is clear. The companion videos are fascinating and should be widely purchased and used past educators and institutions throughout the country to proselytize the unconverted. If classical music is going to survive and thrive, we demand zealous advocates like Joseph Horowitz to proceed beating the pulsate.

Source: https://theamericanscholar.org/a-prophecy-unfulfilled/

0 Response to "Stravinsky Was a Leader in the Revitalization of in European Art Music"

Post a Comment